Learn how to avoid student burnout through energy management and sustainable study habits. Discover mental health strategies that actually work.

Around week ten, you start noticing something in how students move through the world. Their eyes get that particular brightness – the kind that doesn’t come from being well-rested. Movements don’t quite sync with their intent. They laugh at things that aren’t funny. Most people call it stress. Anyone who’s actually spent time in student counseling knows it’s something more specific: it’s the physical evidence of someone running on empty and not yet aware of how empty they actually are.

Over fifteen years of working with college students, one pattern emerges clearer than any other: the kids who burn out aren’t lazy. That’s not the story here. They’re the ones carrying five or six classes when three would be enough, running two clubs simultaneously, working fifteen hours a week, and somehow still frustrated they’re not accomplishing more.

The problem isn’t effort. Nobody’s questioning their work ethic. The problem is that somewhere along the way, nobody taught them to feel the difference between productive energy and just burning through whatever you have left.

Understanding what burnout actually is matters – and most articles skip right past this. Here’s where they get it wrong: burnout isn’t about working too hard. Plenty of students work incredibly hard and come out fine. What actually happens is simpler and more specific. Your energy output stops matching your energy input. And you don’t notice until your nervous system makes the decision for you – which is usually when things have already started breaking down.

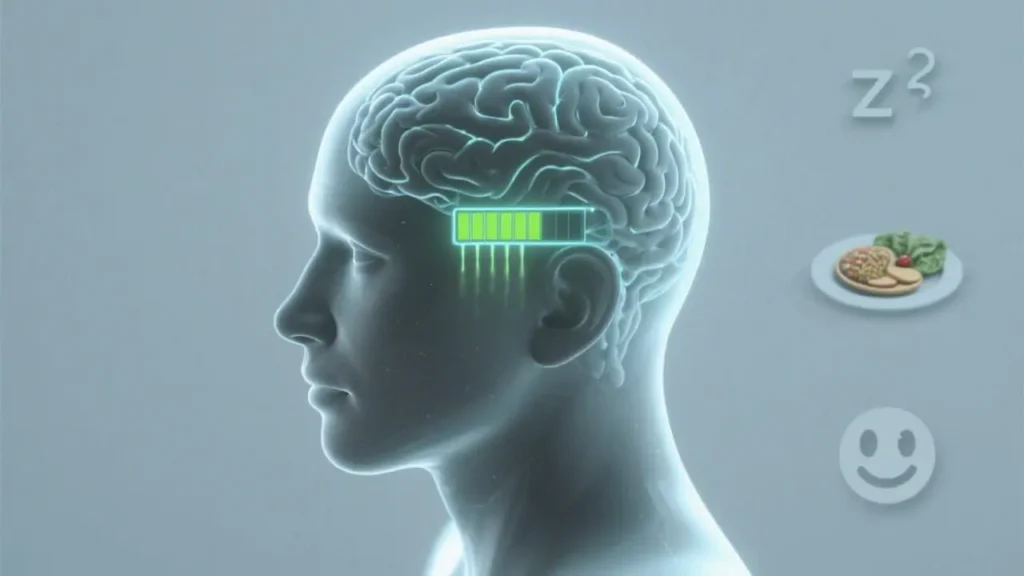

The neuroscience here isn’t complicated. Your prefrontal cortex – that’s the part running decision-making, planning, controlling impulses – it’s expensive. It burns energy like a space heater. When you push past fatigue, skip meals, steal sleep, your brain starts making cuts. First thing to go is nuanced thinking. Then emotional control. Then motivation itself disappears. Your brain’s not being dramatic. It’s rationing resources because you’ve left it no choice.

Stanford University published data in 2023 showing that 67% of undergraduates reported feeling “overwhelming anxiety” during the academic year. But here’s what’s interesting: when researchers dug deeper, they found the anxiety wasn’t proportional to actual workload. It correlated most strongly with perceived lack of control and recovery time. Students who strategically recognize when they’re depleted and pay for research papers to create breathing room often maintain better mental balance than those who push until something breaks.

Most time management advice misses the entire point. Students don’t need better planners. What you actually need is to understand that studying without burning out isn’t about fitting everything in efficiently. It’s about matching what you’re trying to do with the energy you actually have available.

Here’s what works, based on patterns across hundreds of student consultations:

Your energy patterns are individual – what works for someone else won’t necessarily work for you. But track it anyway. Notice when you naturally feel sharp versus when you’re pushing. Use your high-energy windows for genuinely difficult material. Use low-energy periods for review, organization, mechanical tasks. Sounds obvious. Maybe 15% of students actually do it though.

Andrew Huberman’s research found that focused cognitive work operates in roughly 90-minute cycles before your brain hits a wall. Most students ignore this completely and then wonder why hour four of studying feels like pushing rope uphill. Your brain isn’t being difficult. It’s being accurate about its actual limits.

Recovery is where learning actually sticks. Sleep isn’t downtime from studying – it’s when your hippocampus converts what you learned into something permanent. All-nighters before exams don’t sacrifice sleep for better grades. They sacrifice the actual mechanism that lets you retain information. That’s the trade. And it’s not a good one.

Mental health conversations have gotten broader, which is good. But also vaguer. Depression screening and counseling referrals matter. What gets lost is the daily mechanics – how you keep your nervous system regulated when you’re juggling seventeen different demands.

One technique that actually helps: the energy audit. Not tracking time – tracking energy. For one week, rate your mental energy (one to ten) before and after major activities. What emerges is usually surprising. That study group that feels productive? Might drain you. That hour at the climbing gym you think you’re wasting? Might be the only thing keeping Thursday afternoon viable.

When academic pressure becomes overwhelming, essay writing services can provide temporary relief while students regain their balance. The key is using these resources strategically rather than as a constant crutch.

Here’s something most academic advisors won’t say out loud: students who finish strong aren’t necessarily the smartest. They’re the ones who figured out sustainability early.

Look at UCLA or Berkeley – massive research universities where the workload is genuinely intense. The students who thrive aren’t grinding constantly. They’ve learned to be strategic. When to push hard. When to ease back. They know the difference between a challenging assignment worth the cognitive cost and busywork that’ll just drain you for nothing.

MIT tracked student success factors across years. GPA correlated somewhat with test scores coming in. But the strongest predictor – for both academic success and actual wellbeing? How well students managed their energy across the entire semester. The ones who paced themselves outperformed the ones who sprinted.

Theory is nice. Systems actually work. Here’s what sustainable studying looks like:

| Strategy | Why It Works | Common Mistake |

|---|---|---|

| Fixed shutdown time | Gives brain permission to stop processing | Thinking flexibility means “whenever I finish” |

| Weekly review session | Prevents low-level anxiety about forgotten tasks | Only reviewing when panicked before deadlines |

| Energy-based scheduling | Matches task difficulty to mental capacity | Treating all hours as equally productive |

| Strategic saying no | Protects bandwidth for priorities | Saying yes to maintain image, then resenting it |

| Physical movement breaks | Resets nervous system, improves focus | Viewing exercise as separate from studying |

The students who actually build these systems? They’re not superhuman. They just realized earlier – before things broke – that their brain is a biological system with actual limits. Not a computer that should run indefinitely on willpower.

Here’s where this gets tricky. Some stress is necessary for growth. Zero stress means zero challenge means you develop nothing. The goal isn’t eliminating pressure. It’s finding the level where you’re stretched but not shattered.

Think of strength training. Progressive overload works – you lift slightly more than last time, your muscles adapt, you get stronger. But if you max out every single session, ignore recovery, never deload? You don’t get stronger. You get injured.

Academic work follows the same principle. Take the difficult class. Join the demanding research lab. But build in actual recovery. Recognize when you’re in a growth phase versus when you need to consolidate. The students who burn out aren’t the ones who work hard. They’re the ones who never shift gears.

An academic advisor suggests: drop one commitment this semester. The immediate reaction is panic. Everything feels essential. But here’s what actually happens when students create space:

Performance in remaining commitments improves. Sleep normalizes. That constant background hum of anxiety fades. They stop just surviving and start actually enjoying what they’re doing.

One pattern repeats constantly: students overestimate what they can handle in theory and underestimate what they’re capable of when properly resourced. Running at 60% capacity with full energy beats running at 100% capacity while depleted. Every single time.

The real measure of academic success isn’t your semester GPA. It’s whether you finish your degree still curious, still capable of deep work, still mentally healthy enough to actually use what you learned. Burnout doesn’t just tank your grades. It can poison your relationship with learning itself.

Students who learn how to avoid burnout while studying aren’t just protecting their transcript. They’re developing a skill set that matters more in the long run than any specific course content. The ability to work intensely, recover effectively, maintain performance over years – that’s what separates sustainable careers from spectacular flameouts. The most successful students aren’t the ones who sacrifice everything for achievement. They’re the ones who figured out that taking care of your brain is achievement. Everything else follows from that.

Working hard is about effort and intensity. Burnout is about imbalance. You can push incredibly hard and come out fine if your energy input matches your output. But when you’re consistently giving out more than you’re taking in – skipping sleep, meals, and recovery – that’s when your nervous system eventually makes the decision for you. The key difference is whether you’re actually recovering between efforts.

Your brain operates in roughly 90-minute cognitive cycles before hitting a wall. That’s not arbitrary – it’s how your prefrontal cortex actually works. After 90 minutes of focused work, your decision-making and impulse control start running out of fuel. Pushing past that doesn’t make you more productive. It means you’re spending four hours to accomplish what you could do in two focused sessions. Most students ignore this and then wonder why hour four feels impossible.

Sleep isn’t downtime from studying – it’s when your hippocampus converts what you learned into something permanent. When you pull an all-nighter before an exam, you’re not buying more study time. You’re sacrificing the very mechanism that lets information stick. An hour of sleep before an exam is worth more than an hour of cramming. Your brain needs sleep to consolidate learning.

Instead of tracking time, track energy. For one week, rate your mental energy (1 to 10) before and after major activities. You’ll probably discover surprises – that study group might drain you while that hour at the gym might be the only thing keeping your afternoons viable. This tells you which activities actually restore you versus which ones just feel busy. Use that information to protect your high-energy time for difficult work.

There’s a particular look to burnout. Your eyes get too bright, movements feel off, you laugh at things that aren’t funny. But more practically – are you recovering? If you’re pushing hard but getting real rest, sleep, and breaks, that’s stress management. If you’re pushing hard AND skipping sleep, meals, and recovery, that’s burnout building. Track your energy for a week. If everything drains you and nothing restores you, that’s the signal.

Yes, but it depends how you use it. Creating breathing room – whether that’s delegating tasks, outsourcing mechanical work, or using external resources temporarily – gives you space to actually recover. The problem comes when you use that as a permanent crutch instead of a pressure release. Think of it like deloading in strength training. Sometimes you pull back to actually get stronger. The students who thrive recognize when they need that space and use it strategically, then come back with better energy.